Gray Catbird

General Description

Gray Catbirds are medium-sized, slate-gray birds with black caps and tails, and chestnut undertail coverts. Males, females, and juveniles look similar. Gray Catbirds hold their tails cocked up.

Habitat

In all seasons, Gray Catbirds inhabit dense undergrowth dominated by saplings and shrubs. In Washington, they are found most often along streams, where thick, low growth is common, but they can also be found away from water at edges and in other thicketed areas. Thickets of poplar, red-osier dogwood, wild rose, and willow are all commonly inhabited by Gray Catbirds.

Behavior

Gray Catbirds often forage on the ground, flipping leaves aside with their bills. When they forage in the shrub layer, they glean food from foliage and twigs. They sing a discordant series of sounds that can be alternately tuneful and rasping. They are named for their mewing call and are receptive to pishing.

Diet

Gray Catbirds have a varied diet, but primarily eat insects and other small invertebrates during breeding season, and berries and other fruit the rest of the year. They probably eat more vegetable than animal matter over the course of a year.

Nesting

Gray Catbirds are monogamous and form pairs shortly after they arrive on the breeding grounds. They nest in dense, broad-leaved thickets and tangles, or low trees. The female builds the nest, perhaps with material brought by the male. The nest is a large, bulky, open cup, typically supported by horizontal branches and made from twigs, weeds, grass, leaves, and bark strips. It is fashioned into three layers ranging from a coarse outer layer to a fine inner layer. The female incubates 3-4 eggs for 12-14 days. Both parents help brood and feed the young, which leave the nest at 8-12 days. The adults continue to feed the fledglings for up to 12 days after they leave the nest. Gray Catbirds often raise two broods a year, and build a new nest for each brood.

Migration Status

Gray Catbirds are Neotropical migrants that winter in the southeastern US, Mexico, and Central America. Like many other species whose population is centered east of the Rocky Mountains, Gray Catbirds appear to migrate east first and then south, east of the Rockies.

Conservation Status

While the Breeding Bird Survey has recorded a significant population increase in Washington since 1966, the Washington Gap Analysis Project lists the Gray Catbird as a species-at-risk. Its preference for early-successional habitat helps this species to do well in an increasingly human-altered landscape, as road construction, utility-line placement, and development all create habitat. Intensive agriculture, however, reduces shelterbelts that used to provide prime Gray Catbird habitat, and rapid development along coastal wintering grounds has destroyed former habitat also.

When and Where to Find in Washington

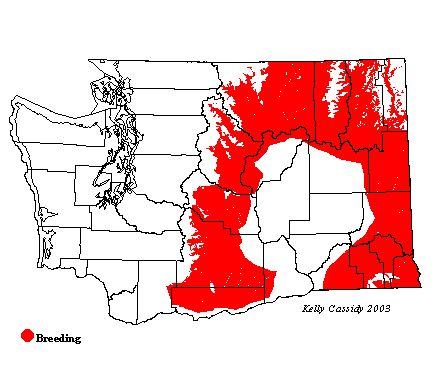

Gray Catbirds are an east-side species. They are most common in major river valleys of far-northeastern Washington, but are present up to the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Gray Catbirds are typically present in Washington from mid-May through early September, but lingering birds have been seen extremely rarely in winter. They can be found in selected thickets along the Yakima River and in tributaries along the Columbia in Kittitas and Yakima Counties.

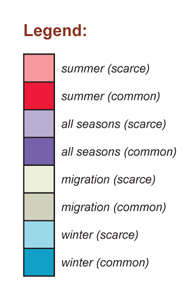

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | ||||||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | F | C | C | C | C | |||||||

| Okanogan | C | C | C | C | U | |||||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | ||||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | U | U | ||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | F | F | F | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map