White-tailed Kite

General Description

The White-tailed Kite was formerly known as the Black-shouldered Kite, until the species was split, with the North American birds taking the new moniker. The White-tailed Kite is a distinctive bird, especially when hovering over open fields. The kite's upperparts are mostly gray, with bold black shoulders. Its tail is white above and below, with a small stripe of light gray down the center of the upper side of the tail. From below, the kite's body appears to be white, with black patches at the wrists and gray-black primaries. Its head is mostly white with red eyes. Juveniles are similar, but have a buffy wash over much of their bodies. The kite's wings are long and pointed, often held in a dihedral during soaring.

Habitat

White-tailed Kites are found in open grasslands with scattered trees for nesting and perching. They are often found along tree-lined river valleys with adjacent open areas, but are not usually found in forests or in clearcuts within forests.

Behavior

Outside of the breeding season, they roost communally, sometimes in groups of more than 100 birds. Density in Washington is not this high, and such large congregations are not seen here. Small groups of around five birds are more common. While hunting, kites often hover over open fields.

Diet

Small mammals, especially voles, make up the majority of the White-tailed Kite's diet.

Nesting

White-tailed Kites form a monogamous pair in December, and the pair stays together year round. Nest building starts in January. They nest in the top of a tree, usually 20-50 feet off the ground. Both members of the pair help build the nest, which is made of twigs and lined with grass, weeds, or leaves. The male brings food to the female as she incubates 4 eggs for 30-32 days. Once the eggs hatch, the male continues to bring food to the brooding female, who feeds it to the young. The young begin to fly at 30-35 days, but don't start catching their own prey for at least another month. The pair may raise a second brood.

Migration Status

While White-tailed Kites have no known regular migration, they do wander widely, especially when prey is scarce.

Conservation Status

During the early 20th Century, the White-tailed Kite had a very restricted range and was threatened with extinction. The population has been growing and expanding its range since then, and has now spread from Texas and California to Oregon, Washington, and other spots throughout the United States. This range expansion is irruptive; they settle in large areas in short periods of time, and seem to follow vole population cycles. There is a sizeable population near the southern coast of Oregon, and birds continue to become more common in Washington. The first known breeding record in Washington is at the Raymond Airport (Pacific County) in 1988.

When and Where to Find in Washington

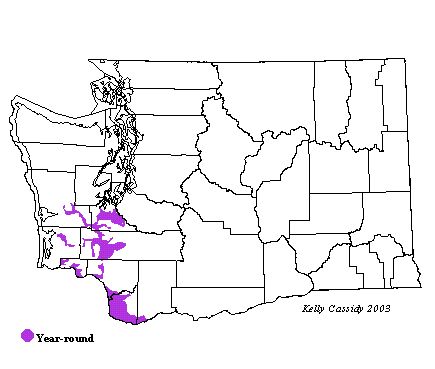

This rare breeder is found year round in wet meadows and tree-lined stream corridors in southwestern Washington, and increasingly farther north in western Washington. In Washington, they are found in higher densities during winter, and thus, seemingly disperse from southern breeding areas. They have nested along the Willapa River and in the Chinook Valley (both Pacific County), by Hanaford Creek and the Chehalis River (both Lewis County). In Wahkiakum County, they have nested along the Skamokawa, Naselle, Deep, and Grays Rivers. They have also bred in a few places in Thurston County. Rarely, non-breeding birds are seen in a few areas of western Washington, as far north as Anacortes (Skagit County).

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | U | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | U |

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

OspreyPandion haliaetus

OspreyPandion haliaetus White-tailed KiteElanus leucurus

White-tailed KiteElanus leucurus Bald EagleHaliaeetus leucocephalus

Bald EagleHaliaeetus leucocephalus Northern HarrierCircus cyaneus

Northern HarrierCircus cyaneus Sharp-shinned HawkAccipiter striatus

Sharp-shinned HawkAccipiter striatus Cooper's HawkAccipiter cooperii

Cooper's HawkAccipiter cooperii Northern GoshawkAccipiter gentilis

Northern GoshawkAccipiter gentilis Red-shouldered HawkButeo lineatus

Red-shouldered HawkButeo lineatus Broad-winged HawkButeo platypterus

Broad-winged HawkButeo platypterus Swainson's HawkButeo swainsoni

Swainson's HawkButeo swainsoni Red-tailed HawkButeo jamaicensis

Red-tailed HawkButeo jamaicensis Ferruginous HawkButeo regalis

Ferruginous HawkButeo regalis Rough-legged HawkButeo lagopus

Rough-legged HawkButeo lagopus Golden EagleAquila chrysaetos

Golden EagleAquila chrysaetos