Bewick's Wren

General Description

Bewick's Wrens are slender with long-tails, gray bellies, and brown backs. Their plumage is less mottled than that of many other wrens. Their tails are barred with a small amount of white at the outer tips. The most distinctive field mark of the Bewick's wren is its bold white eye-line, extending from just over the eye back to the neck.

Habitat

Shrubby areas along clearcuts, rivers, wetlands, and parks, especially in residential and agricultural areas, are the favored habitat of the Bewick's Wren. A mixture of shrub vegetation and open woodland is ideal for this species.

Behavior

An active forager, the Bewick's Wren often climbs about on branches and trunks, probing into crevices to find food. It also feeds on the ground, turning leaves with its bill. Paired birds often forage together in the breeding season. They are usually solitary the rest of the year, although some may remain paired throughout the year.

Diet

Bewick's Wrens eat mainly insects and spiders.

Nesting

The male Bewick's Wren sings to defend his nesting territory and to attract a mate. He starts one or more nests in various cavities, usually natural crevices, old woodpecker holes, nest boxes, or other artificial structures. The female will select one nest and add a soft cup of moss, leaves, hair, feathers, and sometimes snakeskin to the foundation of twigs and bark built by the male. The female incubates the 5 to 6 eggs for 14 to 16 days. The male feeds the female while she is on the eggs, and both parents feed the young. The young leave the nest after about two weeks, but stay together and are fed by the parents for another couple of weeks. The monogamous pair usually stays together through the first brood, and will often raise a second brood, although sometimes they will find new mates for the second brood.

Migration Status

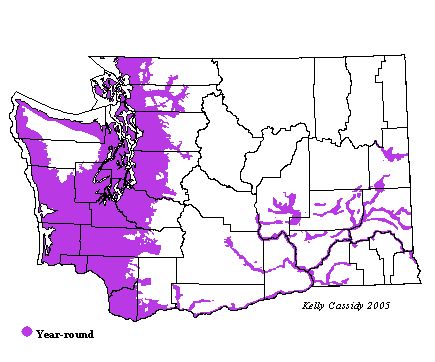

Most Bewick's Wrens in Washington are permanent residents. Some birds from west of the Cascades move east into southeastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and western Idaho in the fall, perhaps in a post-breeding dispersal.

Conservation Status

Bewick's Wren populations are at risk in many parts of the United States, and populations in the eastern part of their range are considered scarce and declining. Much of the population east of the Mississippi is endangered. Most of this decline is blamed on the expansion of House Wrens, who out-compete Bewick's Wrens for nesting sites. Throughout the western part of their range, including western Washington, Bewick's Wrens are widespread and common. Their population has probably increased since the arrival of European settlers due to the resulting forest fragmentation and increased edge habitat. In eastern Washington, they have been expanding their range eastward and northward since 1953.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Bewick's Wrens are common year round at lower elevations throughout western Washington. In southeastern Washington, they are found along major rivers. They can also be found around Spokane. Their population is increasing in eastern Washington, but is still fairly scattered.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| North Cascades | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| West Cascades | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| East Cascades | R | R | R | |||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map